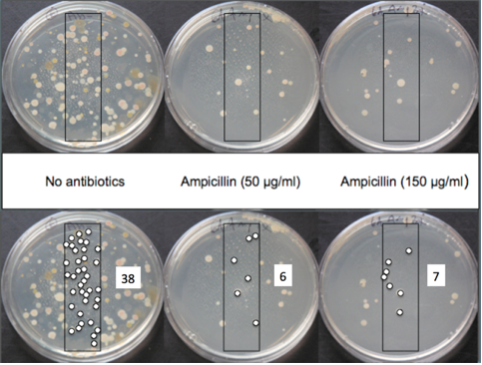

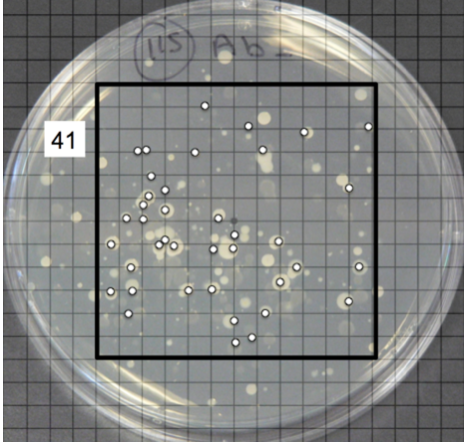

Ideally, for each sample, you have at least two different antibiotic plates (e.g. ampicillin, streptomycin) and a plate without antibiotics. We have discovered that it is important to plate enough water to get somewhere between about 10 to 300 colonies. It is impossible to know how many colonies will grow on the plate for a given amount of water. Typically, you have to do a dilution series in which you plate increasing amount of water onto different plates, ranging from 25µl to 500 µl. We have found that relatively pristine sites require about 250 µl of water whereas sites expected to have a lot of bacteria—near municipalities or agricultural locations—require only 50 to 100 µl of water.

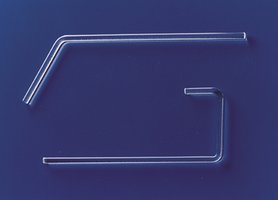

To plate the sample, use a pipette and a sterile tip. Squirt the liquid in the center of the plate and use a plate spreader to gently spread the fluid evenly across the plate. In between spreads, soak the spreader in ethanol and burn away the liquid to sterilize before re-submerging in the sample water. Let the fluid soak in for a couple of minutes and then invert the plate and store at an appropriate temperature (room temperature is typically good).